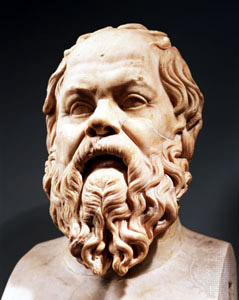

In Plato’s dialogue, Meno, a young man named Meno asks Socrates whether excellence (or virtue) can be taught, or whether it is acquired some other way, or whether one must be born with it. As they explore this question, the conversation soon turns to the nature of knowledge. For teachers whose job it is to impart knowledge to students, the question of how one learns is of utmost importance. It’s no surprise then that Plato’s account of knowledge has always been of special interest to educators.

In Plato’s dialogue, Meno, a young man named Meno asks Socrates whether excellence (or virtue) can be taught, or whether it is acquired some other way, or whether one must be born with it. As they explore this question, the conversation soon turns to the nature of knowledge. For teachers whose job it is to impart knowledge to students, the question of how one learns is of utmost importance. It’s no surprise then that Plato’s account of knowledge has always been of special interest to educators.

It is certainly mysterious that, born knowing nothing, we are able to learn. To explain this mystery, Plato (through the voice of Socrates) proposes that learning is recollection. In Plato’s theory, the soul is in union with the divine before birth, and thus knows all things. After the soul’s incarnation, however, all is forgotten. Thus, human learning is the process by which the soul recollects what it once knew before being encumbered with a body.

To prove this idea, Socrates quizzes the slave boy about a geometric proposition. Never having studied geometry, the slave boy cannot possibly know the solution to the problem. However, Socrates embarks on a series of questions that soon bring the boy to discover the correct answer. Although this exchange is a poor proof for reincarnation, it is a prime example of that teaching method we now call Socratic.

If we are to learn from Socrates’ conversation with the slave boy and become better teachers, we must first consider the nature of what we are trying to impart. In other words, what exactly is knowledge?

In Meno we learn from Socrates that one may have true opinions without having knowledge (85c5), that a man isn’t taught anything other than knowledge (87c), and that knowledge differs from true opinion in that it is tied down by explanation (98a5). Although these statements provide some guidance, they do not provide a useful definition of knowledge.

The word Plato most frequently uses for knowledge is epistéme, which is rather vague, as it can mean skill, experience, knowledge generally, or scientific knowledge. Even when we place the term in the context of Socrates’ questioning the slave boy, it is difficult to completely eliminate any one of these meanings.

Plato uses a different word, however, for knowing: oída (lit. I have seen). This is more helpful. We can immediately see the connection between knowing and recollecting (or recognizing, as I will call it). When we recognize something as true, we have seen it; our seeing either precedes our recognition, or at least occurs simultaneously with it. Our ability to recognize remains mysterious, but our knowing seems to be the result of our seeing and recognizing. And the subject of our knowing is knowledge.

But how is epistéme related to oída? Is it skill in seeing or in recognizing which makes knowledge what it is? This seems unlikely, since it is Socrates’ careful questions, rather than the mental dexterity of the slave boy, that lead him to the answer of the geometry problem. Perhaps then it is the experience of having seen which is the essence of knowledge. This makes better sense in the context of the slave boy. His experience of seeing, as he is lead along by Socrates, is what allows him to recognize the falsity of his wrong answers as well as the truth of the right answer.

After leading the slave boy to solve the geometry problem, Socrates suggests that “he will come to have knowledge without having been taught by anyone, but only having been asked questions, and having recovered this knowledge himself, from himself” (italics added) (85d). Socrates seems not to have been misleading Meno here, since this reflects Socrates’ later claim that one ties down knowledge for himself by working out an explanation, which is the process of recollection or recognition (98a5).

But this creates a problem. Socrates earlier suggested that a man isn’t taught anything but knowledge (87c). But it now seems that a man isn’t taught knowledge at all (98a5). But Socrates’ claim that a man isn’t taught anything but knowledge is preceded by the following words:

“[I]f [excellence] is different from or like knowledge, is it teachable or not––or, as we said just now, capable of being recollected; but let it make no difference to us which term we use––so, is it teachable?”(87c)

The parenthetical qualification in the question suggests that Socrates is comfortable equating guided “recollection” with teaching. Thus, the contradiction can be reconciled if we can understand Socrates to be using the word “teaching” in two different ways. For example, when Socrates was talking to the slave boy, he emphasized that he was not teaching him anything––that is, he was not giving him any new information. Here (98a5), however, the question is not one of information, but rather one of how persons come to knowledge from a set of opinions.

Thus, teaching a student a conclusion does not grant him knowledge. Rather, knowledge is imparted by teaching a student how to reach the conclusion for himself. The construction of the ladder is as much a part of what it means to know as is the truth which he plucks, because it places the fruit of the orchard forever within reach.

March, 2016